This story was originally published as part of the 2021 Annual Report.

In spring of 2020 the Library added to the University’s store of knowledge about the enslaved African Americans who performed work vital to the functioning of UVA in the 19th century. Joining with UVA Landscape Architect Mary Hughes, Chief of Staff of the Division for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Meghan Faulkner, and Assistant Dean and History Professor Kirt von Daacke, a team from the Library conducted research, contributed text, and provided rare images from Special Collections to create a new virtual tour as part of the Walking Tours of Grounds app. The new tour, “Enslaved African Americans at the University of Virginia,” updates a print brochure published earlier by the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University.

The app is part of President Jim Ryan’s initiative to add context to the story of UVA’s past by emphasizing the contributions to University life made by enslaved people. According to team leader Elyse Girard, Executive Director of Library Communications and User Experience, “Access was really at the heart of the creation of this digital tour.” Anyone with internet can use the tour for a view into the world of the enslaved laborers and artisans who excavated the terraced contours of the Lawn in 1817 and literally built the University, laying many thousands of bricks made of clay which they dug from the earth and then molded and fire-hardened in kilns. Viewers can also see how people who were rented to hotelkeepers as property rose from their quarters in basements and outbuildings before daylight every morning to haul water, lay fires, and prepare meals for faculty and students, in many cases laboring behind the high serpentine walls that were constructed to conceal their presence.

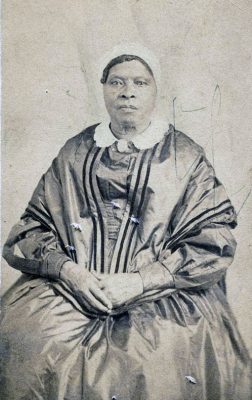

Only 600 names of UVA’s estimated 4,000 enslaved workers are currently known. Among them are husband and wife William and Isabella Gibbons who were divided by enslavement to serve professors in separate households. William Gibbons, a butler, taught himself to read by “observing and listening” to white students. His was a quiet resistance to prohibitions against educating enslaved people. Isabella Gibbons, a domestic servant, likewise risked punishment by teaching their daughter in secret. UVA residence hall Gibbons House is named in their honor.

Free people of color also resisted the social path that whites had mapped out for them. In 1833, seamstress Catherine “Kitty” Foster purchased a little more than two acres which became part of an African American neighborhood known as Canada. An aluminum frame has been erected which casts a shadow tracing the foundation of her house, recovering an idea of the physical space in which people of color lived and worked.

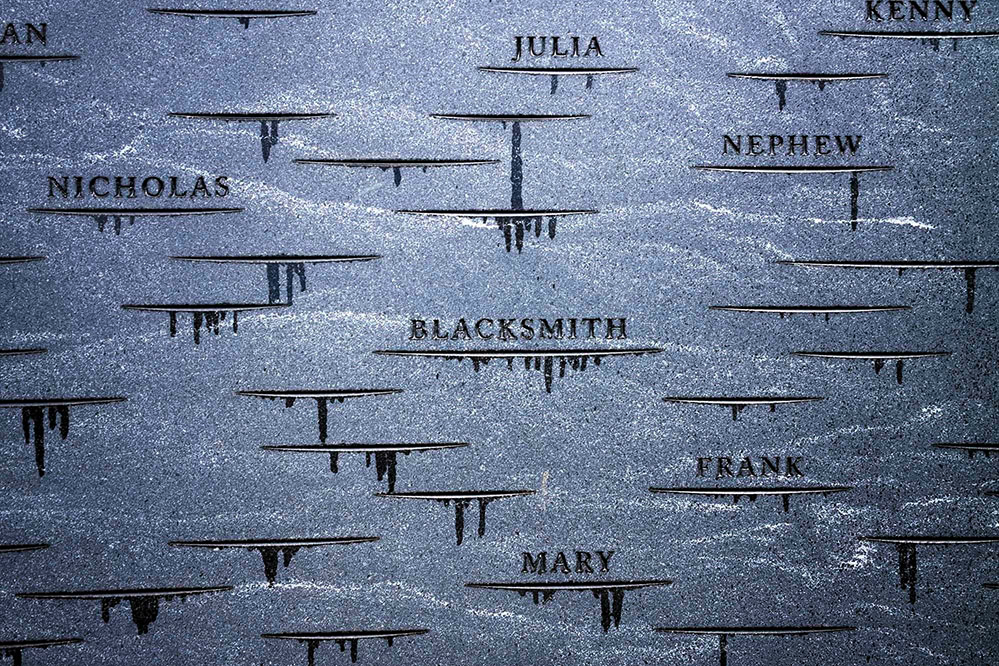

The tour includes a stop at the newly dedicated Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, where hundreds of names of the enslaved at UVA are engraved into the memorial’s innermost ring. Names of enslaved laborers still unknown are represented by slashes etched into the granite of the memorial. Research is ongoing to identify the many individuals not yet recognized, and these “memory marks” serve as placeholders in hopes that the missing names will one day be added.