For Disability Pride Month 2025 — marking the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) — Carla Arton, Keith Weimer, Erin Dickey, Christine Ruotolo, and Bethany Mickel from the UVA Library are proud to spotlight a selection of works that have made the journey from page to screen, offering powerful representations of disability in both written and visual forms. This year’s theme — “adaptation” — invites us to reflect on how stories of disability are told, retold, and transformed when moving from text to film.

Writing about disability is, in itself, a layered act of translation. Whether through memoir, biography, or fiction, the written word attempts to capture the lived experience of disabled individuals — sensory realities, internal landscapes, and social dynamics that often resist simplification. When these stories are then adapted into film, another layer of interpretation is added. What is chosen to be visualized, dramatized, or omitted can deeply shape how audiences come to understand disability — sometimes reinforcing familiar tropes, other times challenging them.

From Helen Keller’s iconic autobiography to Temple Grandin’s firsthand account of autistic perception, and from the poetic voice of Christy Brown to the fictional explorations in “Wonder” and “Still Alice,” this collection spans genres, cultures, and decades. Some adaptations remain faithful, while others diverge dramatically. All raise questions about representation: whose stories get told, how they are framed, and what is gained — or lost — in the process.

As we commemorate 25 years since the passage of the ADA, Disability Pride Month offers a moment to recognize not only policy progress but also the stories that shape cultural understanding. We invite you to explore these works through UVA Library’s holdings —whether in print, on screen, or both — and to reflect on how adaptation can be a powerful vehicle for empathy, visibility, and change. The below list is arranged by original book publication date to reflect evolving narratives of disability, identity, and adaptation across time.

“Story of My Life” by Helen Keller (Doubleday, 1903)

“Story of My Life” by Helen Keller (Doubleday, 1903)

Helen Keller’s memoir is a remarkably eloquent and introspective account of her early life and education. What may surprise readers is her vivid, poetic writing style — she evokes seasons, sensations, and emotional landscapes with precision and beauty. Her prose directly challenges assumptions about what blind and deaf individuals can perceive, understand, and describe. Keller’s rich inner world and her philosophical reflections offer far more than a chronology of events — they present a profound meditation on learning, perception, and connection.

“The Miracle Worker” directed by Arthur Penn (MGM, 1962)

“The Miracle Worker” directed by Arthur Penn (MGM, 1962)

In contrast, “The Miracle Worker” focuses almost exclusively on that early turning point. The film, based on William Gibson’s play, dramatizes the emotional and physical intensity of Keller’s childhood and her teacher’s determined efforts punctuated by the use of black and white film photography. The climactic moment at the water pump is the emotional centerpiece — a creative liberty that expands a brief episode in the memoir into a full narrative arc. Patty Duke’s portrayal of Keller and Anne Bancroft’s of Sullivan both earned Academy Awards, and the film remains a landmark in disability cinema. While the film compresses and dramatizes events, it powerfully communicates the emotional stakes of language acquisition and the teacher-student bond.

— Summary by Carla Arton, Director of Technology Solutions

“Born on the Fourth of July” by Ron Kovic (McGraw-Hill, 1976)

“Born on the Fourth of July” by Ron Kovic (McGraw-Hill, 1976)

Ron Kovic’s 1976 memoir, “Born on the Fourth of July,” and its 1989 film adaptation, powerfully depict his experiences coming to terms with PTSD, paralysis from the chest down, and the moral problems of war. Kovic volunteered for the U.S. Marine Corps in 1964, and was wounded in 1967, returning to the hell of VA hospitals and well-meaning but uncomprehending family and neighbors. The bitter realization that his life would be defined by his disability turned him against the Vietnam War and towards peace and veterans’ rights activism. Kovic’s writing style captures his descent from innocence into disillusion, moral ambiguity, (including war crimes) and ambivalence.

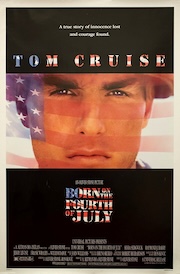

“Born on the Fourth of July” directed by Oliver Stone (Universal Studios, 1989)

“Born on the Fourth of July” directed by Oliver Stone (Universal Studios, 1989)

The movie closely follows the book but adds confrontations with his parents intended to demonstrate Kovic’s embitterment as well as his relationship with a possibly fictional high school sweetheart. Neither the book nor the movie states that Kovic’s activism resolved his physical and mental health problems. However, the movie implies such an “uplifting” resolution, which may reflect distance from the events and what filmmakers believed their audience would want.

— Summary by Keith Weimer, Librarian for History and Religious Studies

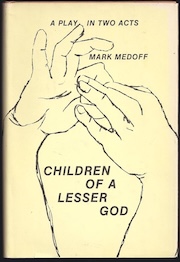

“Children of a Lesser God” by Mark Medoff (Oxford, 1979)

“Children of a Lesser God” by Mark Medoff (Oxford, 1979)

Originally written as a stage play, “Children of a Lesser God” explores the complex relationship between James Leeds, a hearing speech teacher, and Sarah Norman, a deaf woman who refuses to lip-read or speak. The text raises powerful questions about assimilation, autonomy, and how communication is shaped by power and identity. Sarah’s refusal to conform to hearing norms is framed not as resistance but as agency — a central theme that challenged dominant narratives at the time.

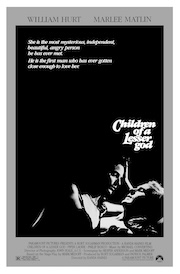

“Children of a Lesser God” directed by Randa Haines (Paramount Pictures, 1986)

“Children of a Lesser God” directed by Randa Haines (Paramount Pictures, 1986)

The 1986 film adaptation remains faithful to the play’s emotional core, expanding it with the intimacy and nuance of visual storytelling. Marlee Matlin’s groundbreaking performance as Sarah earned her an Academy Award — making her the youngest and first deaf performer to win Best Actress. The film’s portrayal of Deaf culture and identity resonated deeply with audiences, although some critics noted that the story remained largely framed through the hearing male protagonist’s perspective. Nevertheless, the film marks a significant milestone in authentic casting and disability representation on screen.

— Summary by Carla Arton, Director of Technology Solutions

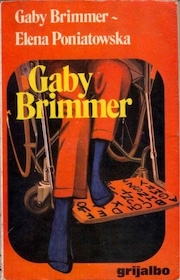

“Gaby Brimmer” by Gabriela Brimmer & Elena Poniatowska (Editorial Grijalbo, 1979, Spanish Edition)

“Gaby Brimmer” by Gabriela Brimmer & Elena Poniatowska (Editorial Grijalbo, 1979, Spanish Edition)

Gaby Brimmer’s biography, co-authored with journalist Elena Poniatowska, tells the story of a Mexican woman born with cerebral palsy who became a poet and disability rights advocate. Unable to speak or move most of her body, Brimmer communicated through a typewriter operated with her left foot and used her life story to highlight broader societal barriers. The book is structured with multiple perspectives — Gaby’s, her family’s, and her caregivers’ — weaving together an intimate and multifaceted portrait of resilience and activism.

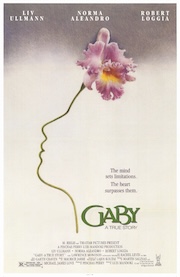

“Gaby: A True Story” directed by Luis Mandoki (RCA/Columbia Pictures, 1987)

“Gaby: A True Story” directed by Luis Mandoki (RCA/Columbia Pictures, 1987)

The 1987 film, “Gaby: A True Story,” adapts this narrative with sensitivity, though it compresses the events of her life into a more traditional biopic structure. The film centers on Gaby’s bond with her caregiver, Florencia, and her fight to live independently and pursue her writing. While some critics felt the film softened the political edge of Gaby’s advocacy in favor of inspirational tropes, others praised it for introducing an international audience to a compelling and underrepresented figure. Norma Aleandro’s portrayal of Florencia received an Academy Award nomination, helping to bring attention to the often-unseen labor of care.

— Summary by Carla Arton, Director of Technology Solutions

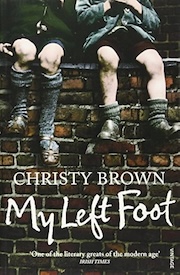

“My Left Foot” by Christy Brown (Minerva, 1954)

“My Left Foot” by Christy Brown (Minerva, 1954)

Christy Brown’s memoir is a raw, candid, and often humorous account of growing up in a working-class Dublin family while living with cerebral palsy. Written with insight and irony, Brown recounts how he learned to write and paint using the only limb he could fully control — his left foot. The book chronicles his personal, social, and artistic development while also offering searing reflections on class, disability, and family.

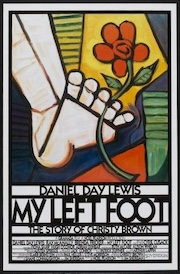

“My Left Foot” directed by Jim Sheridan (Miramax, 1989)

“My Left Foot” directed by Jim Sheridan (Miramax, 1989)

The 1989 film adaptation, starring Daniel Day-Lewis in an Oscar-winning performance, focuses primarily on Brown’s childhood and his early triumphs in communication and art. The film dramatizes his relationship with his mother, who remained steadfast in her belief in his potential, and his eventual rise as a writer and painter. While the adaptation simplifies some of Brown’s later complexities and struggles (particularly with fame, adulthood, and addiction), it preserves the spirit of his early life: grit, wit, and the tenacity to be seen and heard.

— Summary by Carla Arton, Director of Technology Solutions

“Girl, Interrupted” by Susanna Kaysen (Turtle Bay Books, 1993)

“Girl, Interrupted” by Susanna Kaysen (Turtle Bay Books, 1993)

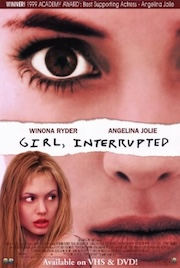

“Girl, Interrupted” is author Susanna Kaysen’s deeply personal memoir of her diagnosis with borderline personality disorder and subsequent stay in a psychiatric facility. Both the book and film adaptation explore the themes of stigma, impact on identity, and the treatment of women in mental health systems through a fragmented structure of memories and medical notes.

“Girl, Interrupted” directed by James Mangold (Columbia Pictures, 1999)

“Girl, Interrupted” directed by James Mangold (Columbia Pictures, 1999)

The film is more linear in nature with an emphasis on the relationships and dynamics of the psychiatric ward set against Kayson’s (played by Winona Ryder) challenges. Both ask us to explore our perceptions of mental illness and consider the complexities of healing and embracing our authentic selves.

— Summary by Bethany Mickel, Teaching and Instructional Design Librarian

“Thinking in Pictures: My Life with Autism” by Temple Grandin (Doubleday, 1995)

“Thinking in Pictures: My Life with Autism” by Temple Grandin (Doubleday, 1995)

In “Thinking in Pictures,” Temple Grandin — a scientist, engineer, and autistic advocate — uses clear, candid prose to describe how her visual thinking shapes every aspect of her life. The memoir offers a rare window into her internal logic, sensory experience, and deep moral commitment to animals. Through vivid explanations and diagrams, she shows how she designs humane livestock systems that balance compassion with efficiency. As one of the few women in a male-dominated industry, Grandin writes not only to inform but to advocate—for better treatment of animals, and for broader understanding of neurodiverse minds.

“Temple Grandin” directed by Mick Jackson (HBO, 2010)

“Temple Grandin” directed by Mick Jackson (HBO, 2010)

The 2010 HBO film adaptation, starring Claire Danes, brings Grandin’s internal world vividly to life. Through stylized visuals and narrated internal monologue, the film effectively conveys the sensory and cognitive differences that define Grandin’s experience. The narrative compresses her life story to focus on key moments of growth, such as her education, career development, and increasing public advocacy. While some technical discussions from the book are simplified, the film was widely praised for its respectful and rich portrayal — earning seven Emmy Awards and a Golden Globe. It is one of the rare cases where an adaptation enhances public understanding of both the individual and the disability it portrays.

— Summary by Carla Arton, Director of Technology Solutions

“The Bear Came Over the Mountain” from “Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage” by Alice Munro (Alfred A. Knopf, 2001)

“The Bear Came Over the Mountain” from “Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage” by Alice Munro (Alfred A. Knopf, 2001)

Originally published as the final story in “Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage” (2001), “The Bear Came Over the Mountain” is a delicate, poignant examination of aging, memory, and long-term love in the face of dementia. Its author, Alice Munro, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2013, uses spare prose to convey vast emotional landscapes with subtlety, revealing Grant’s guilt, past betrayals, and deepening loss as Fiona drifts into affection for another resident.

“Away from Her” directed by Sarah Polley (Lionsgate, 2006)

“Away from Her” directed by Sarah Polley (Lionsgate, 2006)

Sarah Polley’s adaptation, “Away from Her,” is a quietly devastating film that expands the story with visual intimacy and emotional grace. Julie Christie’s portrayal of Fiona earned her an Academy Award nomination, and the film was widely praised for its restraint and humanity. While the adaptation remains faithful to the emotional arc and tone of Munro’s story, it makes certain interpretive shifts — softening some of Grant’s moral ambiguity and deepening the love story aspect. The result is a meditation on love altered by time and illness, offering one of cinema’s most respectful portrayals of cognitive decline and relational endurance.

— Summary by Carla Arton, Director of Technology Solutions

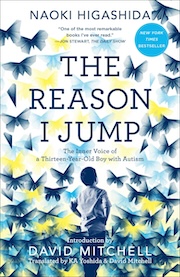

“The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism” by Naoki Higashida (Escor Publishers, 2007)

“The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism” by Naoki Higashida (Escor Publishers, 2007)

Spelling out words and sentences using an alphabet grid, Naoki Higashida, who has non-speaking autism, wrote “The Reason I Jump” in 2007 when he was 13 years old. The book, organized in the form of questions that Higashida answers, is an account of how he perceives, thinks, feels, and empathizes with other people. In explaining his unique experience of time, how he processes language and sound, the relationships between his senses and his emotions, and his body and his mind, Higashida demystifies autism, inviting a greater degree of understanding.

“The Reason I Jump” directed by Jerry Rothwell (Kino Lorber, 2020)

“The Reason I Jump” directed by Jerry Rothwell (Kino Lorber, 2020)

The documentary version of “The Reason I Jump” retains the focus on Higashida’s translation of neurodivergent perception and experience, while also expanding the frame, highlighting the lives, families, struggles, and joys of five other children with autism: Amrit in India, Jestine in Sierra Leone, Joss in the U.K., and Benjamin and Emma in Arlington, Virginia. The film sequences that approximate the perceptual differences between people with non-speaking autism and neurotypical people are particularly effective. When Joss’s father describes Joss’s ability to hear and feel the hum of green electrical boxes from a distance, and his propensity to seek them out, the film score builds to a vibrating, choral hum that becomes almost bodily, at a frequency and pitch that induce attentive calm and pleasure. In this way, the documentary retains and nuances the particularity of Higashida’s experience, while also building a richer sense of the commonalities of perception among people with autism, without flattening their individuality. In perceptual approximations like this, the film extends the book’s work of generating a ground for empathy.

— Summary by Erin Dickey, Librarian for the Arts

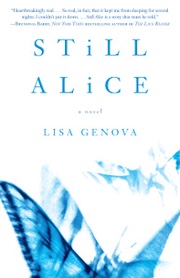

“Still Alice” by Lisa Genova (Gallery Books, 2007)

“Still Alice” by Lisa Genova (Gallery Books, 2007)

Lisa Genova’s debut novel follows Alice Howland, a Harvard linguistics professor diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Written in first-person from Alice’s increasingly unreliable perspective, the novel captures the disorienting and painful erosion of identity and intellect. Genova, a neuroscientist, grounds the story in both emotional depth and scientific realism, giving readers an intimate look at a progressive neurological condition.

“Still Alice” directed by Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland (Sony Pictures, 2014)

“Still Alice” directed by Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland (Sony Pictures, 2014)

The 2014 adaptation features Julianne Moore in a deeply acclaimed, Oscar-winning performance as Alice. The film condenses the narrative to focus more tightly on family dynamics and Alice’s emotional journey, losing some of the intimacy and brutality of decline that the first-person perspective provides from the novel. Though it omits some of the more technical and academic elements of the novel, it preserves the central theme: the struggle to remain oneself while slowly forgetting. Moore’s portrayal was widely praised for its nuance and empathy, and the film significantly raised awareness of Alzheimer’s in the public consciousness.

— Summary by Carla Arton, Director of Technology Solutions

“Wonder” by R.J. Palacio (Alfred A. Knopf, 2012)

“Wonder” by R.J. Palacio (Alfred A. Knopf, 2012)

“Wonder” tells the story of Auggie Pullman, a boy born with Treacher Collins syndrome, as he enters mainstream school for the first time in fifth grade. The novel, structured through multiple points of view, balances Auggie’s experience with those of his family and classmates, offering a layered exploration of difference, kindness, and belonging. Though a fictional story for young readers, it resonated widely with readers of all ages and launched a movement around the phrase “Choose Kind.” Notably, “Wonder” has been included in multiple Virginia public schools’ elementary and middle school curriculum, helping students engage thoughtfully with themes of disability, empathy, and inclusion.

“Wonder” directed by Stephen Chbosky (Lionsgate, 2017)

“Wonder” directed by Stephen Chbosky (Lionsgate, 2017)

The 2017 film adaptation, starring Jacob Tremblay as Auggie and Julia Roberts and Owen Wilson as his parents, stays largely faithful to the novel’s spirit. The film smooths over some of the book’s more complex interpersonal dynamics and centers Auggie’s story more squarely, reducing side characters’ perspectives. While it received criticism for casting a non-disabled actor in the lead role, it was generally praised for its warmth, message, and accessibility. It played a significant role in bringing disability representation into family-oriented mainstream cinema.

— Summary by Carla Arton, Director of Technology Solutions