Guest post by Cecelia Parks, Undergraduate Student Success Librarian.

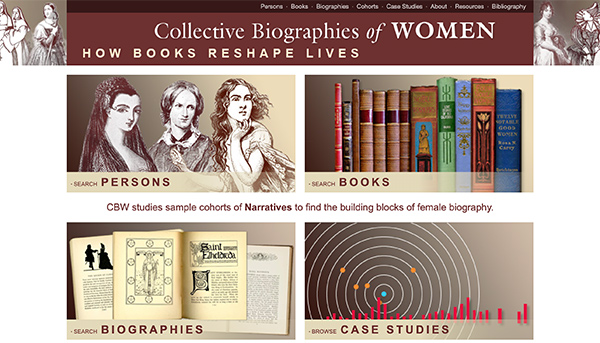

For Women’s History Month, we are highlighting the Collective Biographies of Women, a digital humanities project led by Alison Booth, Professor of English and Academic Director of the Scholars’ Lab. You can access the Collective Biographies of Women here.

Below, Booth answers questions about this massive project, which serves as a database of historical women as well as an annotated bibliography of more than 1200 books.

Q. How would you describe the Collective Biographies of Women (CBW) project?

A. The Collective Biographies of Women (CBW) project began with my work on a book, How to Make It as a Woman (University of Chicago Press, 2004). With the help of many graduate research assistants, I assembled an annotated bibliography of more than 1200 English-language books of three or more short, factual life stories about women. The former E-text Center and then the Scholars’ Lab helped me design and build an online bibliography, and with a fellowship from the Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities, we created a database. It is not a repository of the texts; each collection record in the database is linked to WorldCat and HathiTrust if possible.

The biographies often are skillfully written and curious. Joan of Arc is the all-time favorite subject, according to CBW, with a short biography in 69 different books; but there are many women in war, saints, political leaders, Frenchwomen, all kinds of women overlapping with Joan of Arc’s types. About two-thirds of the subjects are one-offs, some of them so obscure we haven’t located an obituary or other source. I don’t agree with the values of these books, whose authors were confident of the superiority of white, Euro-American, Christian culture, but we can see the purposes they served and recover a rich storehouse of women’s history and changing mores.

Q. How did you become interested in collective biographies of women?

A. I was contributing an essay on short biographies of Queen Victoria, who was gaining scholarly attention in the 1990s, and I had published an article on the pioneering art historian, Anna Jameson. Jameson had published a collection called Female Sovereigns and I needed to know, how many of this sort of book were there?

I just can’t let go of how many versions of women’s lives were circulating well before the start of women’s studies in universities. We’re familiar with the saying, “well-behaved women seldom make history,” now the title of Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s book. I say, “good” women often made history, and, if you believe their biographers, were good housekeepers and mothers, too. Even contemporary feminist scholars assumed that printed accounts only detailed lives of a few notorious or high-ranked figures, and my research with CBW shows a different perspective.

Q. How do you use the Collective Biographies of Women in your own research?

A. I’m generally working on something called prosopography — roughly, a series of parallel lives to make an argument about a group identity, such as a nation or a minority. I have relied on CBW data such as occupational types or networks of tables of contents for many conference papers and keynotes and over a dozen articles and book chapters. I continue to work with graduate students, undergraduate students, and UVA Library staff to continue to develop the CBW project to make it more usable and highlight different minority groups within the biographies.

What are we trying to find out? Broadly, we use the CBW as a tool to categorize and rediscover historical women and their surprising feats, including rescuing passengers from shipwreck and winning a prize for sculpture, who are linked to other resources such as Wikipedia and SNAC (Social Networks and Archival Context). We also want to document the way biographies of different types of women are constructed, using an XML schema on a sample corpus. Narrative elements in CBW include spatial data, and we have experimented with mapping events in the lives as well as the publications.

Q. What would you like to highlight from the Collective Biographies of Women ?

A. You can see how collective biographies resemble the lists of biographies that are put online during Black or Women’s History Month. Over the years, we have focused on the 429 African American women whose biographies are included in CBW texts. We see that the 1890s brought a surge in collective biographies of Black women, followed by renewed advocacy in the 1930s and 1970s.

Some are very well known, such as Mary McLeod Bethune (1875-1955) (see the SNAC biography), who has twelve CBW chapters. Anyone researching this remarkable political and educational leader would find not only the archives through SNAC but also the evidence of changing versions of her life across the 20th century in comparison to other subjects in the same books.

In “Lifting as They Climb” by Elizabeth Lindsay Davis (1933), a “sibling” or subject in the same content list as Bethune, Mrs. Amelia Tolbert, now has a SNAC record that is only populated by a link to CBW. Without dedicating more time to researching the one-off mention of this person, we are constrained by copyright and have not found the text to fill in more information, but she has a record in CBW just like her more well-known counterparts.

Though the books featured in CBW were published between 1830 and 1940, such books have been published for many centuries and continue to be popular today. Here are a few collective biographies of women published in recent years and available through the UVA Library:

“Headstrong: 52 Women Who Changed Science – and the World” (2015), by Rachel Swaby

Rachel Swaby profiles 52 female scientists from Nobel Prize winners to less well-known scientists in “Headstrong: 52 Women Who Changed Science—and the World.” This book is a rebuttal to previous coverage of these women that focused on their domestic roles as wives and mothers.

“Almost Famous Women: Stories” (2015), by Megan Mayhew Bergman

The short stories in Megan Mayhew Bergman’s collection are all based on real historical women who were, as the title suggests, almost famous. Bergman’s stories give them a second chance at fame and shows them in all their human complexity.

“What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories” (2017), by Laura Shapiro

Culinary historian Laura Shapiro profiles six women through their relationships with food in “What She Ate.” These women were famous in their time and most continue to be well-known today, but Shapiro provides a different perspective on their lives in this book.