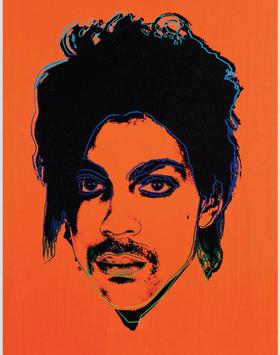

What does an iconic Andy Warhol silkscreen portrait of the musician Prince have to do with the work of libraries? It all relates to the issue of fair use, according to Brandon Butler, the University of Virginia Library’s Director of Information Policy. Last week, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a decision about Warhol’s licensing of “Orange Prince,” as well as two other rulings — Twitter v. Taamneh and Gonzalez v. Google — that addressed platform liability for user content.

We spoke with Butler about the rulings and what they mean for libraries. A copyright lawyer, Butler keeps tabs on open access and fair use issues, court rulings, and the future of AI on his blog, The Taper. Check out his thoughts below!

Q. Can you give brief overviews of the Warhol, Twitter, and Gonzalez cases?

A. I’ll be as brief as I can! Warhol v. Goldsmith is about (you guessed it) Andy Warhol, and in particular it’s about him licensing one of his celebrity silkscreen portraits of Prince for use on a magazine cover. The portrait was based on a photograph, and the photographer objected to Warhol’s use. The Twitter and Gonzalez cases were about whether platforms like Twitter and Google could be held partly liable for terrorist attacks that the plaintiffs said were incited by content hosted on their platforms. In the end, Warhol lost and the tech platforms won.

Q. What were the main concerns about the cases, especially in terms of how they relate to the work libraries do?

A. For Warhol, the library concern was that the Court would revisit its broad and flexible fair use approach and shrink the scope for lawful fair use of in-copyright works. I joke sometimes that libraries are basically warehouses full of legally encumbered objects, and without fair use libraries and their users would be severely limited in what we can do with the information we work so hard to collect and share. We need fair use for preservation, for computer analysis of text, to serve all patrons regardless of disability, to power criticism and commentary, to mount compelling exhibitions, and on and on. If the court had rolled back fair use in Warhol, it would have been a disaster for us.

The connection between libraries, tech platforms, and antiterrorism laws may be less obvious, but it’s still important. The legal arguments in those cases sought to hold Google and Twitter responsible not only for what users posted to their sites, but also for what viewers did outside of the platforms. This is relevant to libraries because many of us (most university libraries, especially) host information on behalf of our communities, and we need reasonable protections from liability for what we host. Otherwise, we wouldn’t be able to support things like Libra or UVA Create, because the risk would be too high. Also, I think it’s generally troubling to hold any information provider responsible for what other people do with the information they provide.

Q. Can you walk us through the rulings handed down last week and what they mean for library workers going forward?

A. In the Warhol case, the Court ruled that the Warhol Foundation (which has managed Warhol’s rights since his death) could not license the Warhol Prince image for use on a magazine cover without Goldsmith’s permission because that was too similar (nearly identical, in fact) to the purpose of Goldsmith’s photograph. In fact, when Warhol initially created his Prince images, he was working on commission for Vanity Fair and the magazine paid a license fee to Goldsmith so that Warhol could use the image. The ruling is extremely narrow for this reason — it really only applies in cases like this where the fair user has the same purpose as the original creator and is competing directly with the original work in its intended market. The scholarly and research uses we see in the library are miles away from this kind of stuff, so I’m pretty confident we won’t see many repercussions from Warhol in our work.

In the Twitter and Gonzalez cases, the court actually dodged what folks thought would be a hot-button issue: whether the court would apply a legal provision called Section 230 that protects online platforms when they might otherwise be liable for user speech. The court dodged the question by finding that the tech companies did nothing wrong here, so there was no need to invoke that platform immunity rule.

Q. Do you foresee challenges to these rulings in the future?

A. In a sense, yes. The Supreme Court is the highest court in the land, of course, so their word on any particular case is final. But the issues they avoided in these cases — when is artistic borrowing unfair, and when should internet companies be shielded from their users’ bad acts — live on, and the lower courts and even Congress are going to be wrestling with them for years to come.

Q. Anything else you’d like to add?

A. It’s interesting that these cases were all basically non-partisan. In an era when trust of the Supreme Court is at an all-time low, and the Court’s conservative supermajority seems to be flexing its power, there are still some issues where you can’t really predict how people will vote based on who appointed them. In Warhol, both the majority and the dissent were written by liberals and joined by conservatives, with a concurrence written by a conservative and joined by a liberal. In the tech platform cases, hard-right justice Clarence Thomas wrote for a unanimous court. This doesn’t mean the court is apolitical, or that it isn’t bitterly divided, but just that there are some areas of law where those divides haven’t asserted themselves.