Guest post coauthored by Cecelia Parks (Undergraduate Student Success Librarian), and Alison Booth, (Professor of English and Academic Director, Scholars’ Lab).

Every year in March, countless blog posts, think pieces, exhibits, and programs are created for Women’s History Month, but the origins of Women’s History Month are rarely explored in these pieces – particularly the entwined development of Black History Month and Women’s History Month.

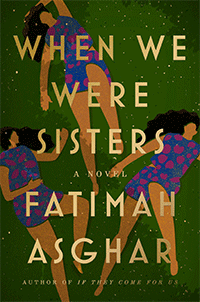

The development of Women’s History Month was closely related to efforts to acknowledge African American history. Carter G. Woodson, who is honored in UVA’s own Carter G. Woodson Institute, founded Negro History Week in 1926. Woodson picked the second week of February for Negro History Week because it contained both Abraham Lincoln’s and Frederick Douglass’ birthdays. Fifty years later, Negro History Week expanded to the whole month of February to become Black History Month.

Women’s History Month followed a similar trajectory. The celebration originated with International Women’s Day in the early 20th century and was then associated with the women’s suffrage movement. In 1978, following the advent of Black History Month, Women’s History Week was first celebrated in California during the week that contained International Women’s Day (March 8). Congress authorized the national celebration of Women’s History Week in 1981, and March was officially designated as Women’s History Month in 1987.

Although Women’s History Month and Black History Month are both aligned with important dates for those communities, the celebrations deliberately take place during the school year (intentionally not in the unsettled time of the start of the year) and have always been aimed at influencing the curriculum. The officially designated months grew out of the same movement that led colleges and universities to develop courses, majors, and centers dedicated to Black and Women’s Studies, as they were then called. These changes came in large part from student demand – including at UVA.

Many public conversations about Black History Month and Women’s History Month focus on biographies of well-known members of those communities. The research areas that came out of the 1970s, however, were not solely focused on famous forebears. The UVA Library has many books related to topics that originated from the research and thought that came out of the women’s movement in the 1960s and 1970s; some recommendations of new and classic fiction and nonfiction books by or about women are below. You can see more recommended books in Virgo.

“When We Were Sisters: A Novel” (2022), by Fatimah Asghar

“When We Were Sisters: A Novel” (2022), by Fatimah Asghar

In her novel, Fatimah Asghar follows three sisters who are left to raise one another after their parents die. The girls’ experiences test what sisterhood means as they also navigate being Muslim women in America.

“Girls Coming to Tech!: A History of American Engineering Education for Women” (2013), by Amy Sue Bix

“Girls Coming to Tech!: A History of American Engineering Education for Women” (2013), by Amy Sue Bix

In “Girls Coming to Tech,” Amy Sue Bix examines the history of women in engineering education, which has historically been perceived as fundamentally and exclusively masculine to a greater degree than other STEM or medical disciplines. She demonstrates that women persevered in studying engineering and diversifying the field even as they were accused of only studying engineering to find husbands (among other obstacles they encountered).

“Women of the Midan: The Untold Stories of Egypt's Revolutionaries” (2019), by Sherine Hafez

“Women of the Midan: The Untold Stories of Egypt's Revolutionaries” (2019), by Sherine Hafez

Hafez brings to light the crucial role women played in the Arab Spring, particularly in Egypt. She uses firsthand testimony to demonstrate that women protested in the street and used the revolutionary moment to renegotiate many of the structures that governed their lives. Hafez also uses these women’s experiences to discuss the role of the gendered body in revolutionary struggles.

“Feminism Is for Everybody: Passionate Politics (Second Edition)” (2015), by bell hooks

“Feminism Is for Everybody: Passionate Politics (Second Edition)” (2015), by bell hooks

In hooks’ short primer on feminism, she answers the question “what is feminism?” while critically evaluating contemporary feminist movements and discussing issues related to feminist ideology, such as reproductive justice, sexual violence, race, class, and sexuality.

“Your Silence Will Not Protect You” (2017), by Audre Lorde

“Your Silence Will Not Protect You” (2017), by Audre Lorde

“Your Silence Will Not Protect You” is the first major collection of Audre Lorde’s poetry and prose, which are as relevant today as they were when they were first published decades ago. Lorde was an intersectional feminist thinker and writer who described herself as “Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet” and wrote about race, gender, sexuality, class, and more.

“Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice” (2018), by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

“Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice” (2018), by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha explores the disability justice movement, which centers the leadership and experiences of sick, disabled, trans, and Black and brown people, in this short collection of essays. Among the topics she explores, Piepzna-Samarasinha calls for “collective access” – making access a joy and responsibility for everyone.

“Transgender History: The Roots of Today’s Revolution (Second Edition)” (2017), by Susan Stryker

“Transgender History: The Roots of Today’s Revolution (Second Edition)” (2017), by Susan Stryker

Stryker’s foundational work covers major events, movements, and leaders in American transgender history from the mid-20th century to today, providing context for today’s fights for transgender rights and demonstrating that trans folks have always been here.

“Knocking Myself Up: A Memoir of My (in)fertility” (2022), by Michelle Tea

“Knocking Myself Up: A Memoir of My (in)fertility” (2022), by Michelle Tea

Michelle Tea shares the story of her journey to pregnancy as a 40-year-old, uninsured queer woman in this intimate, funny memoir. She writes about her strong friendships, the world of fertility medicine