NOTE: As of March 2023, the free version of the Twitter API no longer allows read requests. This means the instructions below to create a developer account, access Twitter, and download tweets no longer works as written. If you have a paid "Basic" tier or higher then these instructions may work for you, but we have not verified this.

In this article, I will walk you through why a researcher or professional might find data from Twitter useful, explain how to collect the relevant tweets and information from Twitter in R, and then finish by demonstrating a few useful analyses (along with accompanying cleaning) you might perform on your Twitter data.

Part One: Why Twitter Data?

To begin, we should ask: why would someone be interested in using data from Twitter? What is it that tweets and their accompanying data can tell us about the world around us? Specifically, while there are a plethora of interesting research questions stemming from Twitter data–how people communicate, when, and why–what are some potentially business-minded practical uses of such data?

As someone with a background in both politics and political science, I am especially interested in how an elected official might make sense of and use data that is available for them on Twitter. This is particularly relevant in light of the political events of recent years in which Twitter is often the forum where political actors both make announcements and speak to one another. In addition, Twitter also serves as a medium from which constituents can make direct contact with their elected officials. While tagging the president or a senator may sometimes feel like shouting into the wind, there is always a chance you might receive a personal response. In addition, in recent years, individuals who have had an especially bad experience with a company will sometimes take to Twitter to air their grievances and demand a response. Indeed, in the often looping chain of customer service lines, Twitter can sometimes be a more efficient way to actually speak with a company representative.

Thus, for a company or a political representative who is seeking to better understand their clients or constituents, Twitter can be a great forum to get first-hand feedback. Bypassing the use of surveys, Twitter data can offer an intimate and real-time look into the minds of consumers, pointing an organization to where they’re going wrong (although, admittedly, not as commonly to what they’re doing well) and what’s important to their consumer base. While the clientele on Twitter skews younger, it is not as young as one might expect.1

So, let’s create a hypothetical situation. Say that I am an individual working for Rodney Davis, a House of Representatives member from the 13th congressional district in Illinois. In 2018, Representative Davis faced a close race, winning by less than a percentage point.2,3 As a member of his staff, I might be assigned the task of helping to better understand why Davis almost lost and what constituents are still unhappy about–a question about which Twitter can easily provide large swathes of data. Rather than reading through all of this data myself, I can use R to quickly break down and understand the tweets Rep. Davis receives.

In the next section, I will explain how to obtain this data. In the final section, I will demonstrate a few techniques–such as network analysis–which may be helpful in understanding what is important to constituents on Twitter.

Part Two: How to Collect Twitter Data

In order to download data from Twitter for use in R, the first step is to set up an application with Twitter. To do this, go to: https://developer.twitter.com/en/apps. Once there, create an account (you can simply sign in with your personal Twitter account if you already have one) and click “Create an app” in the upper right hand corner. You will have to give your application a name, such as “Exploring Text Mining,” a description, and a URL. For the description, you might write that you are learning more about R, are using the data for a course, or write a little bit about the project you’re working on. The URL can be linked to an external site or can simply be your main Twitter profile page.

Once you finish these steps and gain approval–something which is often nearly instantaneous, but can take several days if you’re unlucky–you are now ready to download data from Twitter to R. In order to download selected tweets, you first need to install and then load the twitteR package in R.

library(twitteR)

Next, return to your application page and click on the “Details” tab. Here, you will find your consumer key, consumer secret, access token, and access secret values. Copy each of these long letter-number values and substitute them in the appropriate spots in the code below. Then, run the setup_twitter_oauth command to link your Twitter account to your R operations.

consumer_key <- "XXXXX"

consumer_secret <- "XXXXX"

access_token <- "XXXXX"

access_secret <- "XXXXX"

setup_twitter_oauth(consumer_key, consumer_secret,

access_token, access_secret)

Now that R is connected to the Twitter application you made, you need to make a choice. Which text will signal the data which is most interesting to you? In this case, we are interested in tweets which have tagged Rodney Davis, using “@RodneyDavis”. That is because we want to see what individuals are saying to Representative Davis, rather than those about him (#RodneyDavis) or by him (those coming from the account @RodneyDavis). Thus, in this case we search for the text “@rodneydavis.” The command is not case sensitive, so it will still capture any capitalization combination which might exist. I have chosen here to include 1,000 tweets, but you can choose whatever value feels sufficient for your work. I then save this data–which includes 16 pieces of information, such as retweet counts, favorite counts, the username of the tweeter, the text, and the date for each of the 1,000 tweets–to a list I call “davis_list.”"

davis_list <- searchTwitter("@rodneydavis", n=1000)

To make this data more easily explored and to prepare it for cleaning, I then convert the list to a data frame named “davis_df” using the dplyr package. In this command, I first turn each part of the list into its own individual data frame with 16 columns (recall the 16 pieces of information above). This is done with the lapply(davis_list, as.data.frame) portion. Then, I combine all of these 1 row data frames into a single, 1000 row data frame so that we have all of the the tweets and their identifying information in a single data frame together. Once the data is in this format, it is easier for us to see what the values of each column look like and decide upon any cleaning we might want to undertake.

library(dplyr)

davis_df <- bind_rows(lapply(davis_list, as.data.frame))

If you are unable or unwilling to collect the data directly from Twitter, you can run the following code to import the data as a CSV file.

library(readr)

davis_df <- read_csv("https://static.lib.virginia.edu/statlab/materials/data/davis.csv")

Part Three: How to Analyze Twitter Data

With our Twitter data in this easy-to-explore format, we now need to think about what kinds of analyses might be interesting or informative for us to undertake.

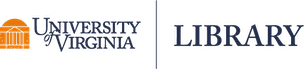

First, we might be interested in when individuals tweet the most. The data that we obtained here ranges from April 19 to April 25 of 2019, a six day period. On what days or at what times are users most active? The simplest way to learn this information is to simply make a density plot.

In its current state, the created variable is in the format of year-month-day-hour-minute-second. In order to see which days and times individuals tweet most frequently with the “@rodneydavis” tag, we must first separate out a distinct date and hour variable from the current format. In the code below, I use the lubridate package–a useful package for dealing with time variables in the POSIXct class–to create new variables for date and hour. The day() and hour() commands, when applied to a variable of class POSIXct, efficiently draw out their respective elements. I then assign this to a new, similarly named variable in the davis_df.

library(lubridate)

davis_df$date <- day(davis_df$created)

davis_df$hour <- hour(davis_df$created)

With these new variables created, I now can create a couple of useful visualizations. In the first plot, I set the x-axis to be the date, while the y-axis displays the volume of tweets. The geom_density() portion designates the graph as displaying density. I load the ggplot2 package beforehand in order to run these operations and create the date_plot. After running the code, we can see that the 19th and the 23rd had the highest volume of tweets with @rodneydavis–although we do not yet know why.

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(davis_df, aes(x = date)) +

geom_density()

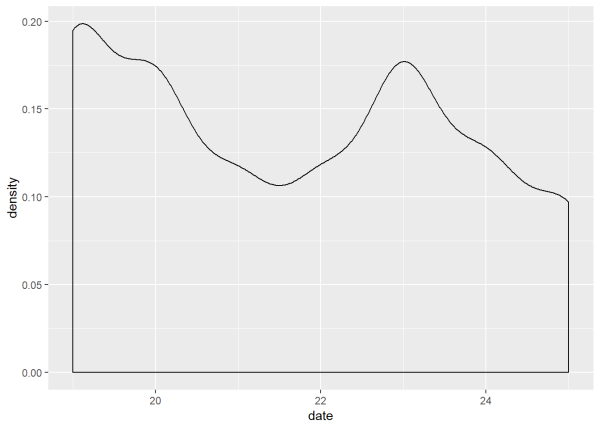

Now, I look at what time of day users tweet most frequently with the “@rodneydavis” designation. I use the same code as above, with only a slight modification in the x-axis value to hour instead. This graph shows us that the highest volume of tweets are sent out during the hours of 12:00am and 2:00pm. Interesting to know, but not necessarily informative without context.

ggplot(davis_df, aes(x = hour)) +

geom_density()

Another question we might be interested in is what words are used most commonly when individuals are speaking negatively about Rodney Davis, and what words are associated with positive speech? However, in order to understand the sentiment of the speech used in these tweets and pinpoint particular words, we must first perform some cleaning operations. This cleaning will make our data smaller and thus easier to manage, as it will remove uninteresting stop words such as “the” and “it,” along with irrelevant punctuation and capitalization.

We will begin our cleaning by removing any Twitter mentions. In other contexts, we might be curious to know how often users respond to one another. However, here we are only interested in content, not user interaction. Thus, we use the gsub() function to find the pattern of @ signs followed by alphabetical characters; this is designated as @[[:alpha:]]* in code. Then, we write "" with no text in between to indicate subbing occurrences of the first pattern with nothing. This is followed by davis_df$text to designate the column within the object that we would like to modify.

davis_df$text <- gsub("@[[:alpha:]]*","", davis_df$text)

Now, we need to load the tm package. It is through this package that we will do the rest of our data cleaning.

library(tm)

Then, we must convert the portion of our data frame containing text into a corpus object. As with several other text mining packages, the text must be in a corpus object in order for tm to recognize it. In this step, we draw out only the “text” column because we are uninterested in cleaning the rest of the data with tm.

text_corpus <- Corpus(VectorSource(davis_df$text))

Next, we want to convert all of our text to lowercase. This move ensures that text with differing capitalization will all be standardized when we perform our analysis later. This is done through the tm package with the tm_map command. The syntax of the tm_map function asks that we put the object we are modifying first (here, that is text_corpus) and the operation we wish to perform second (tolower).

text_corpus <- tm_map(text_corpus, tolower)

Then, we want to remove mentions of “rodneydavis.” We want to remove this piece of text because, logically, since we selected tweets based on their inclusion of “@rodneydavis,” having it in our text tells us nothing interesting about their content. Just as with turning all of the words to lowercase, we use the tm_map() command to first indicate the object we are performing our function on, then the act we would like to do. However, in this case, we also specify which word(s) we would like to remove by including them in parentheses. We will also include “rt” and “re” because knowing a tweet is a retweet from another user or a reply to another other is not substantively useful for us. In addition, when the tweets we downloaded, every “&” sign was turned into “amp.”4 Thus, we remove this abbreviation as well.

text_corpus <- tm_map(text_corpus, removeWords,

c("rodneydavis", "rt", "re", "amp"))

Now, we will remove stop words. Stop words are common words that usually do not carry significance for the meaning. As mentioned above, this might include words such as “the,” and “it.” Just as with removing “@rodneydavis,” here we will use tm_map(), followed by the object we are operating on, the operation we would like to do (removeWords), and the text that will be removed (stopwords("english")).

text_corpus <- tm_map(text_corpus, removeWords,

stopwords("english"))

Finally, we will want to remove punctuation. This is because punctuation is not relevant to our analysis of the sentiment contained within these tweets. We have already removed all of the @ signs, but we still need to remove the other punctuation that remains. This does include removing the # sign, too. Just as with the @ symbol, in a different study we might be interested in knowing what hashtags are most common. However, the content of hashtags will still be reported with this operation, just without the accompanying symbol.

text_corpus <- tm_map(text_corpus, removePunctuation)

Now, we need to turn this cleaned corpus back into a data frame, which we will then merge with our initial davis_df data frame. In the code below, I create a column named text_clean which takes on the content of the text_corpus. Then, I convert this set of data into a data frame with the data.frame() command, including stringsAsFactors = FALSE in order to keep the text as class character. This last step will be crucial in our future analyses.

text_df <- data.frame(text_clean = get("content", text_corpus),

stringsAsFactors = FALSE)

Then, I bind text_df with davis_df using the cbind.data.frame function. I specify the latter data.frame portion, because cbind alone in this case will coerce all of the columns to the same class. In this case, that would be the factor class, which is not conducive to sentiment analysis.

davis_df <- cbind.data.frame(davis_df, text_df)

Now, with our cleaned data in hand, we are ready to begin our sentiment analysis.

Utilizing the SentimentAnalysis package, we can simply apply the command analyzeSentiment() to quickly create a data frame which contains the sentiment scoring for each tweet. Contained in this data frame are 13 sentiment scores from four different dictionaries: GI, HE, LM, and QDAP. Running the analyzeSentiment() command compares the text of the tweets with these various dictionaries, looking for word matches. When there are matches with positively or negatively categorized words, the tweet is given a corresponding sentiment score, which is located in the davis_sentiment data frame.

library(SentimentAnalysis)

davis_sentiment <- analyzeSentiment(davis_df$text_clean)

Returning to our hypothetical role as an individual working to understand what Rodney Davis’ constituents are displeased with, we want to isolate the tweets which contain more negative than positive sentiment.

To begin this process, I first pare down the davis_sentiment data frame to contain only the sum sentiment analysis results–that is, removing the unnecessary accompanying “Negativity” and “Positivity” measures. This is done with the select() command in the dplyr package, naming only the relevant variables we would like to keep. Once performed, the data we are working with is smaller and easier to understand.

davis_sentiment <- dplyr::select(davis_sentiment,

SentimentGI, SentimentHE,

SentimentLM, SentimentQDAP,

WordCount)

Having no theoretical reason to rely on any of these dictionaries more than the others, I will now create a mean value for each tweet’s sentiment level, leaving us with a single sentiment value for each tweet. Using the mutate() command, I create a new variable which takes the average of every row. Since I kept the word count in the last command, we must specify in the code below not to include the 5th column in the mean.

davis_sentiment <- dplyr::mutate(davis_sentiment,

mean_sentiment = rowMeans(davis_sentiment[,-5]))

Finally, we remove each of the now unnecessary sentiment measures from the davis_sentiment data frame, leaving us only with word count and the mean measure. We will proceed to merge this data frame with the preexisting davis_df to pair the sentiment measure with each tweet.

davis_sentiment <- dplyr::select(davis_sentiment,

WordCount,

mean_sentiment)

davis_df <- cbind.data.frame(davis_df, davis_sentiment)

Having paired tweets and their respective mean sentiment measures, we now will strip the data set of any tweets which are more positive than negative. Remember, we are interested in why constituents are unhappy with Rep. Davis, not why they support him. Thus, we use the filter() function to create a new data frame with only tweets whose mean value is less than 0.

This command gives a data frame with only 306 rows remaining.

davis_df_negative <- filter(davis_df, mean_sentiment < 0)

nrow(davis_df_negative)

[1] 303

Now, we want to know what topics are most commonly contained within these tweets. There are two ways we can go about understanding this. The first is to look only at frequency. That is, which words are the most common? The second is to form topic clusters which show us which words are most associated with one another.

To do the first, finding the most frequent words, we need to begin by separating out each word. We will do this using the quanteda package. This is another text analysis package with a few simple tools to help us get the answers we want. After loading quanteda, we then use the tokens() command to separate out each word individually.

library(quanteda)

davis_tokenized_list <- tokens(davis_df_negative$text_clean)

Next, we turn this list object into a document feature matrix with the dfm() command. This turns every row into a document (which in this case is a tweet) and every term (or word) into a column. Finally, we are able to use the colSums() command to get the count of use for every word, which we assign to the vector “word_sums.” Using length() on this vector, we are able to tell that there are 1040 values, or 1040 words.

davis_dfm <- dfm(davis_tokenized_list)

word_sums <- colSums(davis_dfm)

length(word_sums)

[1] 1040

In order to then see which words are the most frequent, we create a new data frame from the “word_sums” values, with the data.frame() function. In accordance with the data.frame() syntax, both “word” and “freq” are given as column names, while the number of rows is dictated by the number of values; in this case, that is the 1040 from above. We set row.names = NULL to avoid each row taking on a name, which in this case would be the words themselves. We also add stringsAsFactors = FALSE in order to keep the words in character class.

freq_data <- data.frame(word = names(word_sums),

freq = word_sums,

row.names = NULL,

stringsAsFactors = FALSE)

Finally, we create a data frame which is sorted by the order() function and accompanying decreasing = TRUE argument from most to least common words. We select the freq column to sort on to achieve this goal. So that our created object is a data frame, rather than a vector, we put everything inside of the freq_data[ , ] brackets. This arrangement, in which the brackets and comma designate [row, column], tells R to keep the columns as they are, but to rearrange the order of the rows. That is, to maintain the integrity of the object as a data frame, but reorder it sorting on frequency.

sorted_freq_data <- freq_data[order(freq_data$freq, decreasing = TRUE), ]

Examining the sorted_freq_data object tells us that some of the most common words with substantive meaning are “tax,” “taxes,” “impeachment,” “tariffs,” and “muellerreport,” giving us a brief but only minimally informative look at what tweeters are concerned with or want to speak to Rep. Davis about. It seems that perhaps a different technique than word frequency could give us more insight.

Thus, we turn now to our second approach, seeking to form topic clusters to see which words are most related to one another. These clusters require interpretation by us: we will have to see what kind of connections we can make between the words. However, when put in conjunction, some of these words may be more informative than the single word frequencies we already calculated.

To begin, we must first convert our data into a data term matrix object. This necessitates converting our object first to the corpus format from its existing data frame class. We do this by using the Corpus() command from the tm package, indicating the location of the material being used to create our corpus. In this case, that is the 19th column of the davis_df_negative, which is text_clean.

We then swiftly turn this corpus into a document term matrix with the DocumentTermMatrix() command.

davis_corpus_tm <- Corpus(VectorSource(davis_df_negative[,19]))

davis_dtm <- DocumentTermMatrix(davis_corpus_tm)

Next, we lower the sparsity of this dtm. Just as with our earlier cleaning operations, this is done to speed up the time it will take to form our clusters. Additionally, we are uninterested in words which are so uncommon that they don’t appear in at least 2% of the documents–this is communicated by the complementary 0.98 threshold assigned to the removeSparseTerms() command. We can check if this is a reasonable amount of sparsity by looking at the number of words remaining after the next step. Here, it is 81–somewhere around 100 is often a good rule of thumb.

Finally, we convert this document term matrix into a data frame called davis_df_cluster. This is done by first turning the dtm into a matrix and then a data frame with the as.matrix() and as.data.frame() commands.

davis_dtm <- removeSparseTerms(davis_dtm, 0.98)

davis_df_cluster <- as.data.frame(as.matrix(davis_dtm))

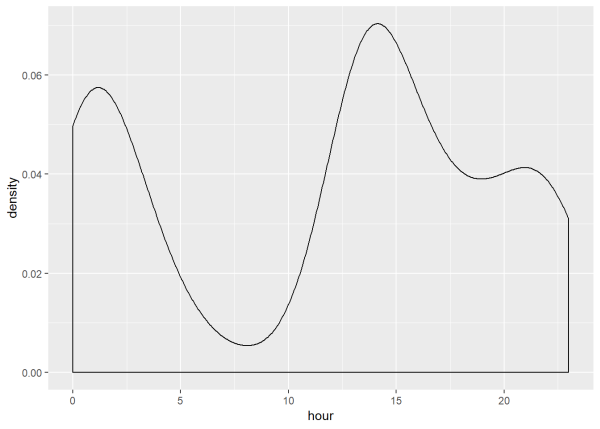

Now, we will create clusters using a technique called Exploratory Graph Analysis (EGA, for short). Install and load the package EGAnet. EGA is a form of network analysis which creates word clusters based on correlation. Words which are most correlated with one another will appear in the same cluster (also called a dimension) and it is up to the user to interpret these results.

# install.packages("EGAnet")

library(EGAnet)

Having installed and loaded our packages, we now use the command EGA() to initially generate our clusters, utilizing the “davis_df_cluster” data frame. This will generate a visual indicating the words in each node, with the colors demarcating clusters.

ega_davis <- EGA(davis_df_cluster, cor = "spearman")

While this 11-clustered graphic is pretty to look at, it often abbreviates the words and thus is not as informative as it could be. Thus, we select dim.variables from within the ega_davis object to tell us which words belong to which cluster. We have to construct our own meaning from these clusters; for example, both cluster 2 and 3 appear to refer to the Mueller Report–maybe constituents wanted Rep. Davis to take action related to the release of the report. Cluster 6 seems to point to the lack of public town halls held by Rep. Davis–a common critique by his opponents. Cluster 9 is a little bit more difficult to decipher but contains words like “corrupt,” “fraud,” “impeach,” and “hiding.” While the presence of “impeach” seems to indicate this cluster is about President Trump, this cluster might encourage a staffer to look back at the tweets themselves to see what tweets with these words in them typically reference. Finally Cluster 11 relates to the Barr Report and the untruths some constituents thought it contained (see: “spun,” “false,” “deliberately,” “mis…”). Through the result of EGA, it seems we can get a better sense of what Rep. Davis’s constituents are unhappy about than only looking at the frequencies.

ega_davis$dim.variables

items dimension

greatbike greatbike 1

taxes taxes 1

… … 1

office office 1

tax tax 1

year year 1

just just 1

even even 1

president president 1

cut cut 1

t… t… 1

get get 1

attack attack 1

campaign campaign 1

partisan partisan 1

now now 1

election election 1

children children 1

mueller mueller 2

davis davis 2

money money 2

report report 2

see see 3

eyes eyes 3

13voter 13voter 3

barr barr 3

currently currently 3

deliberately deliberately 3

false false 3

mis… mis… 3

reading reading 3

spun spun 3

decatur decatur 4

rodney rodney 4

know know 5

ops ops 5

photo photo 5

cancer cancer 5

issues issues 5

morning morning 6

muellerreport muellerreport 6

s… s… 6

town town 7

held held 7

hall hall 7

county county 7

fall fall 7

il13 il13 7

last last 7

indivisible indivisible 8

around around 8

easier easier 8

explaining explaining 8

going going 8

hang hang 8

impeachment impeachment 8

neck neck 8

try try 8

republicans republicans 9

donnie donnie 9

years years 9

everything everything 9

tariffs tariffs 9

think think 9

’s ’s 10

time time 10

corrupt corrupt 10

fraud fraud 10

hiding hiding 10

impeach impeach 10

misses misses 10

treasury treasury 10

<U+2066><U+2069> <U+2066><U+2069> 10

elected elected 11

constitutional constitutional 11

duty duty 11

evident evident 11

fear fear 11

official official 11

recognize recognize 11

What we’ve explored today are only a few ways we can make use of Twitter data, but I hope they prove helpful as you engage with your own exploratory analysis.

References

- Feinerer I, Hornik K (2023). tm: Text Mining Package. R package version 0.7-11, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tm.

- Gentry J (2015). twitteR: R Based Twitter Client. R package version 1.1.9, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=twitteR.

- Golino H, Christensen AP (2022). EGAnet: Exploratory Graph Analysis – A framework for estimating the number of dimensions in multivariate data using network psychometrics. R package version 1.1.1. https://github.com/hfgolino/EGAnet

- Grolemund G, Wickham H (2011). Dates and Times Made Easy with lubridate. Journal of Statistical Software, 40(3), 1-25. https://www.jstatsoft.org/v40/i03/.

- Wickham H, François R, Henry L, Müller K, Vaughan D (2023). dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. R package version 1.1.2, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr.

Leah Malkovich

Statistical Consulting Associate

University of Virginia Library

May 3, 2019

Updated July 8, 2020

- https://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/↩

- Full disclosure: I am originally from this district and voted in this election.↩

- https://www.nytimes.com/elections/results/illinois-house-district-13↩

- This anomaly was found by perusing the

davis_df.↩

For questions or clarifications regarding this article, contact statlab@virginia.edu.

View the entire collection of UVA Library StatLab articles, or learn how to cite.