Five years ago this week, community organizers, activists, students, and residents of Charlottesville stood up to an unprecedented wave of far-right hate and terror. Several hundred white supremacists marched at the University of Virginia and in downtown Charlottesville as part of the “Unite the Right” rally, events that led to violence and three deaths. Immediately following the weekend of Aug. 11 and 12, 2017, senior leaders at the University of Virginia Library asked curators and archivists to collect both physical and digital materials related to the rally.

Library staff got to work, gathering accelerants and tiki torches that had been thrown in bushes; white supremacist propaganda left in driveways; and posters and banners from students, faculty, staff, and community members who had counter-protested the white nationalists. UVA curators teamed up with the Jefferson-Madison Regional Library to collect images, videos, and stories about the rally from the local community. At the same time, digital preservationists were gathering rally-related tweets, photos, and postings online before they disappeared, including hateful speech from places like 4chan. It was challenging work.

“We realized that we hadn’t prepared for this. Although we had been working towards developing workflows for collecting born-digital content, we didn’t have the infrastructure in place to support the technological challenges or emotional challenges of the work,” said Kara M. McClurken, the Library’s Director of Preservation Services. “From my own perspective, as a manager, I wasn’t sure how to best support my staff who were being asked to do things like stabilize the tiki torches used to threaten and harm our students and a Library colleague.”

This crash course in what McClurken describes as “collecting in times of crisis” led the Library to form a Digital Collecting Emergency Response Group, which sought advice from other institutions that had experienced tragedies in their communities. “After the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida, a group of archivists found themselves feeling similarly,” she said, and they asked the Society of American Archivists to explore ways to provide support for communities documenting in times of crisis. The Library also applied for and received a grant from the nonprofit LYRASIS, which they used to develop resources and toolkits to help institutions be better prepared to implement digital collecting strategies during and after crises.

Now, UVA Library has an official Digital Collecting Emergency Response team, led by McClurken, who also serves as co-chair of the Society of American Archivists’ Crisis, Disaster, and Tragedy Response Working Group. “Within UVA Special Collections, this experience (as well as larger discussions in the archival community) has changed our way of viewing our work — we have a group of folks who now meet regularly to discuss a trauma-informed approach to our spaces and collections, and to consider the impact of harmful or difficult content,” she said.

Many of the digital items UVA Library staff collected in the days after rally are now available to the public in the “University of Virginia Collection on Events in Charlottesville, VA, August 11-13, 2017,” a 20 gigabyte digital archive, containing everything from a video of white supremacists marching up the Rotunda steps the night of Aug. 11, to a recollection of a helicopter that hovered over the city for hours on Aug. 12, to a compilation of statements by institutional leaders at Virginia colleges and universities condemning hateful ideologies.

McClurken emphasized that it was a multi-departmental Library team that gathered the materials from many different sources, noting specifically the efforts of Joseph Azizi, the Library Stacks Coordinator in Special Collections; Stacey Lavender, the Project Digital Archivist; and Lauren Work, the Digital Preservation Librarian. “I was amazed at all the ‘firsts’ they accomplished to get this collection ready,” she said. “This type of collecting in times of crisis often requires many hands.”

New exhibition centers on alumni and community activist experience

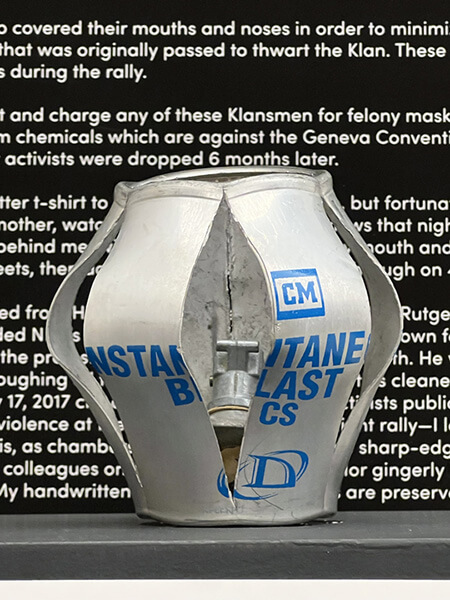

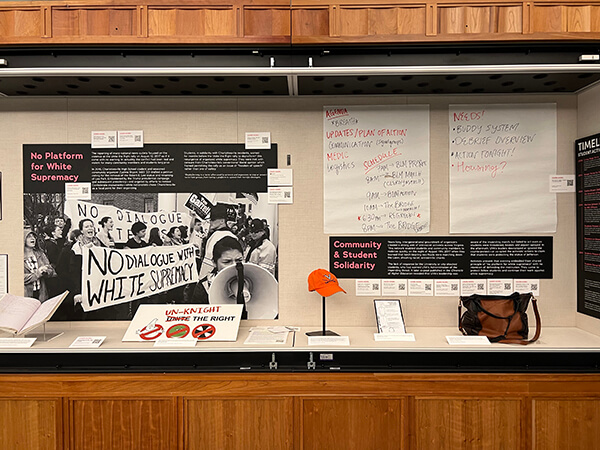

Today, the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library is launching a new exhibition, “No Unity Without Justice: Student and Community Organizing During the 2017 Summer of Hate,” which will be on display in the First Floor Gallery through October 29, 2022. The exhibition is distinctive in that it was largely curated by UVA alumni who took part in the anti-fascist counter-protests in the summer of 2017 when they were students.

“In recent years, we’ve sought curatorial partnerships with the people and places on whom we place the lens of focus,” said Curator of University Library Exhibitions Holly Robertson. “Every curator brings a perspective — and necessarily their experience — to every exhibition. ‘No Unity Without Justice’ may be unique in that the curators have offered us a first-person perspective based on being fully embedded on the frontlines of Charlottesville just five short years ago.”

The 37-item exhibition provides personal narratives of the curators’ experiences, as well as those of various Charlottesville community activists. It was primarily curated by Kendall King, a 2018 UVA alum, artist, and community organizer; in partnership with Jalane Schmidt, a UVA associate professor of religious studies; with guest alumni curators Natalie Romero, Hannah Russell-Hunter, and Memory Project postdoctoral fellow Gillet Rosenblith. King and Romero pitched the exhibition idea to Special Collections when they were still students.

The exhibit is in partnership with the UVA Democracy Initiative’s Memory Project, and the study of democracy is a priority research area in the University’s 2030 Strategic Plan. Schmidt, who directs The Memory Project, said the exhibition aligns with the Project’s mission to sponsor events that promote more inclusive, democratic narratives of history. She worked with the curators to ensure the exhibition’s historical accuracy; all sources are cited in the exhibition and many objects include QR codes linking to news articles, Charlottesville City Council meeting minutes, and a successful civil lawsuit against organizers, promoters, and participants of the Unite the Right rally. “I have been impressed by the students’ energy in documenting these events,” she said. “Memory is not always pretty; it can be painful.”

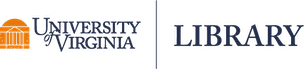

The exhibition includes not only the personal items of the alumni curators and community members (a tear gas canister launched at counter-protestors during a Ku Klux Klan rally in Charlottesville in July 2017; a shoulder bag used by an activist as a makeshift shield to protect students around the Jefferson statue on August 11; a student notebook with poetry, songs, sketches, and research from summer 2017), but also objects and papers related to UVA student activist history, dating back to the 1969 founding of the UVA Black Students for Freedom group.

“I hope visitors will also gain an appreciation for Charlottesville and the University’s deep, rich organizing tradition that has resulted in many victories in the past decades,” said alum curator Russell-Hunter. “It was really gratifying to articulate my experiences as a survivor — including observations and analyses that I have literally been thinking about for years — with the knowledge that it was going to reach a wide audience. I’m grateful to the Special Collections staff for giving us the space to create an honest narrative of the events of the summer of 2017.”

Robertson said she hope the exhibition is “a cathartic thing. That’s how we set up the space — it’s a place to move through another person’s experience and also to reflect on your own, whether you were there on Aug. 11 and 12 or not. We’re deeply grateful to the curators for entrusting us with their archives and their stories.”

Take a look at some of the objects in the “No Unity Without Justice” exhibit below.

“No Unity Without Justice” remains on view until October 29, 2022. See Library hours and parking information.

Press inquiries: Elyse Girard, elyse@virginia.edu.