The Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test is often described as the non-parametric version of the two-sample t-test. You sometimes see it in analysis flowcharts after a question such as "is your data normal?" A "no" branch off this question will recommend a Wilcoxon test if you're comparing two groups of continuous measures.

So what is this Wilcoxon test? What makes it non-parametric? What does that even mean? And how do we implement it and interpret it? Those are some of the questions we aim to address in this post.

First, let's recall the assumptions of the two-sample t test for comparing two population means:

- The two samples are independent of one another

- The two populations have equal variance or spread

- The two populations are normally distributed

There's no getting around #1. That assumption must be satisfied for a two-sample t-test. When assumptions #2 and #3 (equal variance and normality) are not satisfied but the samples are large (say, greater than 30), the results are approximately correct. But when our samples are small and our data skew or non-normal, we probably shouldn't place much faith in the two-sample t-test.

This is where the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test comes in. It only makes the first two assumptions of independence and equal variance. It does not assume our data have have a known distribution. Known distributions are described with math formulas. These formulas have parameters that dictate the shape and/or location of the distribution. For example, variance and mean are the two parameters of the Normal distribution that dictate its shape and location, respectively. Since the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test does not assume known distributions, it does not deal with parameters, and therefore we call it a non-parametric test.

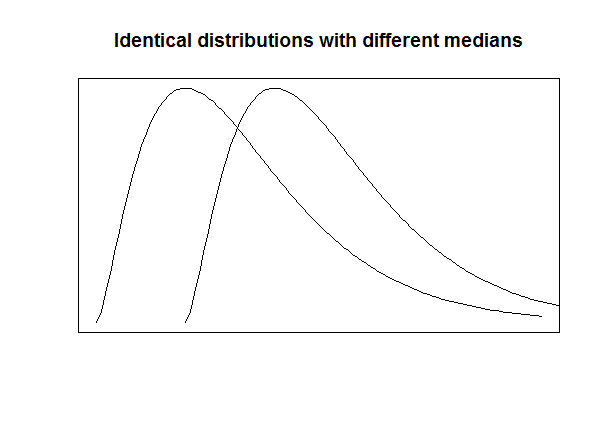

Whereas the null hypothesis of the two-sample t test is equal means, the null hypothesis of the Wilcoxon test is usually taken as equal medians. Another way to think of the null is that the two populations have the same distribution with the same median. If we reject the null, that means we have evidence that one distribution is shifted to the left or right of the other. Since we're assuming our distributions are equal, rejecting the null means we have evidence that the medians of the two populations differ. The R statistical programming environment, which we use to implement the Wilcoxon rank sum test below, refers to this as a "location shift".

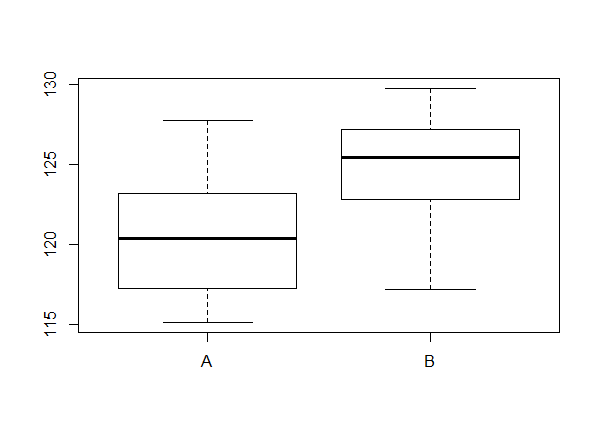

Let's work a quick example in R. The data below come from Hogg & Tanis (2006), example 8.4-6. It involves the weights of packaging from two companies selling the same product. We have 8 observations from each company, A and B. We would like to know if the distribution of weights is the same at each company. A quick boxplot reveals the data have similar spread but may be skew and non-normal. With such a small sample it might be dangerous to assume normality.

A <- c(117.1, 121.3, 127.8, 121.9, 117.4, 124.5, 119.5, 115.1)

B <- c(123.5, 125.3, 126.5, 127.9, 122.1, 125.6, 129.8, 117.2)

dat <- data.frame(weight = c(A,B),

company = rep(c("A","B"), each=8),

stringsAsFactors = TRUE)

boxplot(weight ~ company, data = dat)

Now we run the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test using the wilcox.test() function. Again, the null is that the distributions are the same, and hence have the same median. The alternative is two-sided. We have no idea if one distribution is shifted to the left or right of the other.

wilcox.test(weight ~ company, data = dat)

Wilcoxon rank sum test

data: weight by company

W = 13, p-value = 0.04988

alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not equal to 0

First we notice the p-value is a little less than 0.05. Based on this result we may conclude the medians of these two distributions differ. The alternative hypothesis is stated as the "true location shift is not equal to 0". That's another way of saying "the distribution of one population is shifted to the left or right of the other," which implies different medians.

The Wilcoxon statistic is returned as W = 13. This is NOT an estimate of the difference in medians. This is actually the number of times that a package weight from company B is less than a package weight from company A. We can calculate it by hand using nested for loops as follows (though we should note that this is not how the wilcox.test() function calculates W):

W <- 0

for(i in 1:length(B)){

for(j in 1:length(A)){

if(B[j] < A[i]) W <- W + 1

}

}

W

[1] 13

Another way to do this is to use the outer() function, which can take two vectors and perform an operation on all pairs. The result is an 8 x 8 matrix consisting of TRUE/FALSE values. Using sum on the matrix counts all instances of TRUE.

sum(outer(B, A, "<"))

[1] 13

Of course we could also go the other way and count the number of times that a package weight from company A is less than a package weight from company B. This gives us 51.

sum(outer(A, B, "<"))

[1] 51

If we relevel our company variable in data.frame dat to have "B" as the reference level, we get the same result in the wilcox.test output.

dat$company <- relevel(dat$company, ref = "B")

wilcox.test(weight ~ company, data = dat)

Wilcoxon rank sum test

data: weight by company

W = 51, p-value = 0.04988

alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not equal to 0

So why are we counting pairs? Recall this is a non-parametric test. We're not estimating parameters such as a mean. We're simply trying to find evidence that one distribution is shifted to the left or right of the other. In our boxplot above, it looks like the distributions from both companies are reasonably similar but with B shifted to the right, or higher, than A. One way to think about testing if the distributions are the same is to consider the probability of a randomly selected observation from company A being less than a randomly selected observation from company B: P(A < B). We could estimate this probability as the number of pairs with A less than B divided by the total number of pairs. In our case that comes to \(51/(8\times8)\) or \(51/64\). Likewise we could estimate the probability of B being less than A. In our case that's \(13/64\). So we see that the statistic W is the numerator in this estimated probability.

The exact p-value is determined from the distribution of the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Statistic. We say "exact" because the distribution of the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Statistic is discrete. It is parametrized by the two sample sizes we're comparing. "But wait, I thought the Wilcoxon test was non-parametric?" It is! But the test statistic W has a distribution which does not depend on the distribution of the data.

We can calculate the exact two-sided p-values explicitly using the pwilcox function (they're two-sided, so we multiply by 2):

For W = 13, \(P(W \leq 13)\):

pwilcox(q = 13, m = 8, n = 8) * 2

[1] 0.04988345

For W = 51, \(P(W \geq 51)\), we have to get \(P(W \leq 50)\) and then subtract from 1 to get \(P(W \geq 51)\):

(1 - pwilcox(q = 51 - 1, m = 8, n = 8)) * 2

[1] 0.04988345

By default the wilcox.test() function will calculate exact p-values if the samples contains less than 50 finite values and there are no ties in the values. (More on "ties" in a moment.) Otherwise a normal approximation is used. To force the normal approximation, set exact = FALSE.

dat$company <- relevel(dat$company, ref = "A")

wilcox.test(weight ~ company, data = dat, exact = FALSE)

Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction

data: weight by company

W = 13, p-value = 0.05203

alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not equal to 0

When we use the normal approximation the phrase "with continuity correction" is added to the name of the test. A continuity correction is an adjustment that is made when a discrete distribution is approximated by a continuous distribution. The normal approximation is very good and computationally faster for samples larger than 50.

Let's return to "ties". What does that mean and why does that matter? To answer those questions first consider the name "Wilcoxon Rank Sum test". The name is due to the fact that the test statistic can be calculated as the sum of the ranks of the values. In other words, take all the values from both groups, rank them from lowest to highest according to their value, and then sum the ranks from one of the groups. Here's how we can do it in R with our data:

sum(rank(dat$weight)[dat$company=="A"])

[1] 49

Above we rank all the weights using the rank() function, select only those ranks for company A, and then sum them. This is the classic way to calculate the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test statistic. Notice it doesn't match the test statistic provided by wilcox.test(), which was 13. That's because R is using a different calculation due to Mann and Whitney. Their test statistic, sometimes called U, is a linear function of the original rank sum statistic, usually called W: \[U = W - \frac{n_2(n_2 + 1)}{2}\] where \(n_2\) is the number of observations in the other group whose ranks were not summed. We can verify this relationship for our data

sum(rank(dat$weight)[dat$company=="A"]) - (8*9/2)

[1] 13

This is in fact how the wilcox.test function calculates the test statistic, though it labels it W instead of U.

The rankings of values have to be modified in the event of ties. For example, in the data below 7 occurs twice. One of the 7's could be ranked 3 and the other 4. But then one would be ranked higher than the other and that's not correct. We could rank them both 3 or both 4, but that wouldn't be right either. What we do then is take the average of their ranks. Below this is \((3 + 4)/2 = 3.5\). R does this by default when ranking values.

vals <- c(2, 4, 7, 7, 12)

rank(vals)

[1] 1.0 2.0 3.5 3.5 5.0

The impact of ties means the Wilcoxon rank sum distribution cannot be used to calculate exact p-values. If ties occur in our data and we have fewer than 50 observations, the wilcox.test() function returns a normal approximated p-value along with a warning message that says "cannot compute exact p-value with ties".

Whether exact or approximate, p-values do not tell us anything about how different these distributions are. For the Wilcoxon test, a p-value is the probability of getting a test statistic as large or larger assuming both distributions are the same. In addition to a p-value we would like some estimated measure of how these distributions differ. The wilcox.test() function provides this information when we set conf.int = TRUE.

wilcox.test(weight ~ company, data = dat, conf.int = TRUE)

Wilcoxon rank sum test

data: weight by company

W = 13, p-value = 0.04988

alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-8.5 -0.1

sample estimates:

difference in location

-4.65

This returns a "difference in location" measure of -4.65. The documentation for the wilcox.test() function states this "does not estimate the difference in medians (a common misconception) but rather the median of the difference between a sample from x and a sample from y."

Again we can use the outer function to verify this calculation. First we calculate the difference between all pairs and then find the median of those differences.

median(outer(A,B,"-"))

[1] -4.65

The confidence interval is fairly wide due to the small sample size, but it appears we can safely say the median weight of company A's packaging is at least -0.1 less than the median weight of company B's packaging.

If we're explicitly interested in the difference in medians between the two populations, we could try a bootstrap approach using the boot package. The idea is to resample the data (with replacement) many times, say 1000 times, each time taking a difference in medians. We then take the median of those 1000 differences to estimate the difference in medians. We can then find a confidence interval based on our 1000 differences. An easy way is to use the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles as the upper and lower bounds of a 95% confidence interval.

Here is one way to carry this out in R.

First we load the boot package, which comes with R, and create a function called med.diff() to calculate the difference in medians. In order to work with the boot package's boot() function, our function needs two arguments: one for the data and one to index the data. We have arbitrarily named these arguments d and i. The boot function will take our data, d, and resample it according to randomly selected row numbers, i. It will then return the difference in medians for the resampled data.

library(boot)

med.diff <- function(d, i) {

tmp <- d[i,]

median(tmp$weight[tmp$company=="A"]) -

median(tmp$weight[tmp$company=="B"])

}

Now we use the boot() function to resample our data 1000 times, taking a difference in medians each time, and saving the results into an object called boot.out.

boot.out <- boot(data = dat, statistic = med.diff, R = 1000)

The boot.out object is a list object. The element named "t" contains the 1000 differences in medians. Taking the median of those values gives us a point estimate of the estimated difference in medians. Below we get -5.05, but you will likely get something different.

median(boot.out$t)

[1] -5.05

Next we use the boot.ci() function to calculate confidence intervals. We specify type = "perc" to obtain the bootstrap percentile interval.

boot.ci(boot.out, type = "perc")

BOOTSTRAP CONFIDENCE INTERVAL CALCULATIONS

Based on 1000 bootstrap replicates

CALL :

boot.ci(boot.out = boot.out, type = "perc")

Intervals :

Level Percentile

95% (-9.399, -0.100 )

Calculations and Intervals on Original Scale

We notice the interval is not too different from what the wilcox.test() function returned, but certainly bigger on the lower bound. Like the Wilcoxon rank sum test, bootstrapping is a non-parametric approach that can be useful for small and/or non-normal data.

R session details

The analysis was done using the R Statistical language (v4.5.2; R Core Team, 2025) on Windows 11 x64, using the package boot (v1.3.32).

References

- Canty A and Ripley B (2022). boot: Bootstrap R (S-Plus) Functions. R package version 1.3-28.1.

- Hogg R.V. and Tanis E.A. (2006). Probability and Statistical Inference, 7th Ed, Prentice Hall.

- R Core Team (2016). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.

Clay Ford

Statistical Research Consultant

University of Virginia Library

January 5, 2017

Updated May 25, 2023

For questions or clarifications regarding this article, contact statlab@virginia.edu.

View the entire collection of UVA Library StatLab articles, or learn how to cite.