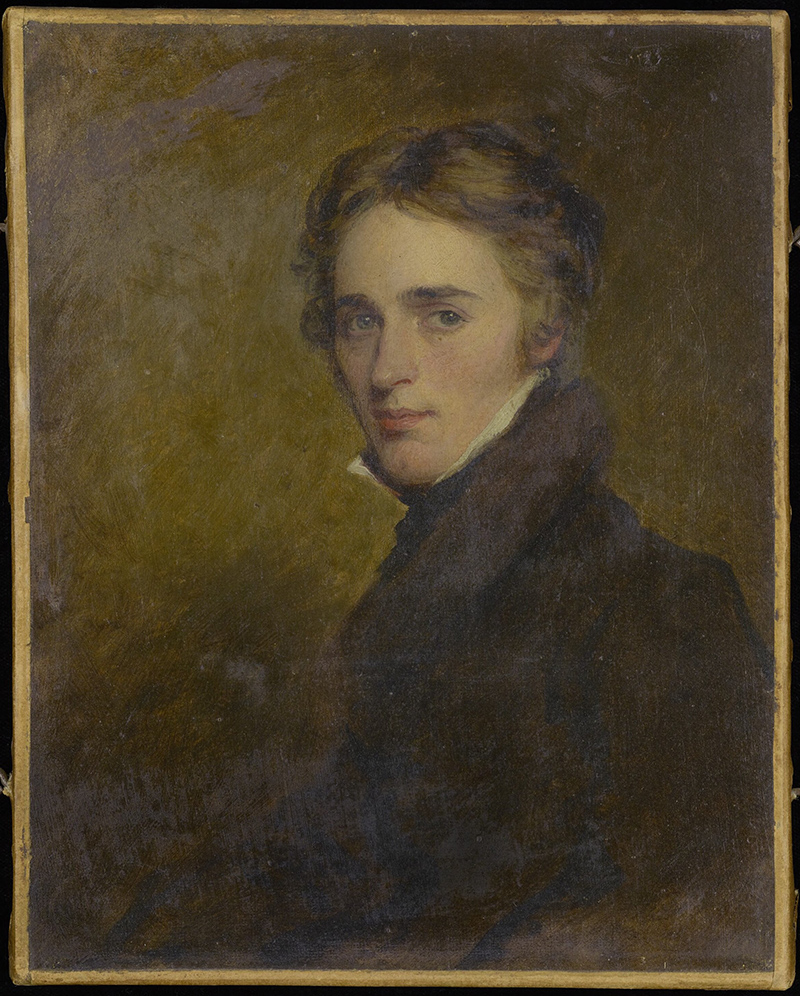

A new exhibition now open in the First Floor Gallery of UVA’s Harrison Institute and Small Special Collections Library makes a bold and compelling claim: a portrait long held in the Library’s collections has for nearly a century been misidentified and is now believed to be the most accurate image of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley in existence. Arranged to appear almost like an evidence board on a detective show, the exhibition calls on the viewer to look with their own eyes, asking, “What do you see?”

Shelley, who is now regarded as one of the most influential English poets of the Romantic movement, was not well known in his lifetime. The author of the utopian allegory “Queen Mab” and the sonnet “Ozymandias” (a poem so endurably influential it was referenced in the television shows “Succession” and “Breaking Bad”), Shelley lived a radical life. He was an atheist and a vegetarian who promoted sexual freedom and an end to aristocratic privilege. Due to backlash against his beliefs, Shelley self-exiled in Italy, where he drowned in 1822 at the age of 29.

Few portraits of Shelley were ever made in his lifetime; an 1819 portrait of the poet by amateur Irish painter Amelia Curran is the best known and was copied by several artists. UVA Library’s new exhibition “Portrait of a Poet—Revisited: William Edward West’s Percy Bysshe Shelley” makes the claim that a portrait by American painter William Edward West was for years misidentified as an image of the English writer Leigh Hunt and is actually a portrait of Shelley, based on a sketch composed just days before Shelley’s death.

“It’s an amazing thing to have this portrait, arguably the best painting we have of Shelley and the only one done by a professional portraitist, here at UVA,” said Andrew Stauffer, a UVA professor of English and co-curator of the exhibition. “We’ve relied on the Curran portrait to characterize Shelley in the past and he’s come off as rather angelic and somewhat infantilized in certain ways,” he said. “This picture shows him as political, interested, older — he’s got the gray hair in his sideburns; it’s captured right before his death. It’s a way of seeing Shelley that we haven’t had access to.”

The story behind the portrait

About a year ago, Stauffer, who specializes in literary Romanticism, was at work on a forthcoming biography of the poet Lord Byron. Deep in research mode, Stauffer was examining an 1822 portrait of Byron done by William Edward West when he came upon another West portrait that gave him pause. The man in this second portrait, in Stauffer’s eyes, very much resembled Percy Bysshe Shelley, who was a peer of Byron’s. Stauffer began delving into that portrait’s history and current location and discovered it was held just “100 yards away” from where he was working: in UVA’s Special Collections Library.

The portrait first appeared in 1905, when it was published, along with a narrative of its provenance written by Nellie P. Dunn, in The Century magazine. Dunn, who ultimately donated the portrait to UVA Library, wrote that, according to West’s nephew, West met Shelley in the summer of 1822 at Byron’s summer house in Montenero, Italy, and was “so impressed by the man’s charming individuality” that he “slyly made a sketch of him.” This was less than a week before Shelley drowned in a shipwreck in the Tyrrhenian Sea. At some point after Shelley’s death, according to the narrative, West made the oil painting from his “sly sketch.”

The portrait was accepted as Shelley for much of the early 20th century. But in 1940 the scholar Newman Ivey White published an influential biography of Shelley in which White objected to the authenticity of the West portrait, insisting it was instead a portrait of Leigh Hunt, another peer of Byron’s. White suggested that West invented his story opportunistically, once Shelley’s fame had risen in the mid-19th century. “I believe White got it wrong with regard to West,” Stauffer writes in a forthcoming article in the Keats-Shelley Journal. “In my view, it is the best portrait of Percy Shelley that has come down to us, and 20th-century Shelleyans were right to accept it as genuine.”

The exhibition systematically dismantles White’s theory by examining physical evidence in a way that White wasn’t able to in his time. “It uses technology that wasn’t available in the 1940s when White made his argument,” Stauffer said. “He was working with low-quality black and white photos, all reproduced in old books. Whereas we can put various portraits side by side, magnify them, and zoom in.” The visual resemblance to all other existing Shelley portraits is crucial, Stauffer said, as well as a short 1828 magazine article on Shelley that stated West had indeed met the poet in Italy and claimed that Shelley “had also the most wonderful-looking head ever seen alive on our earth.”

“Shelley was not famous when that article was published,” Stauffer said. “There was no reason West would make that up for self-aggrandizement. To me, this is the smoking gun that suggests he definitely met Shelly, observed him physically, and likely sketched him, which is what artists tend to do.” In the face of testimony reported from the painter himself, Stauffer writes in his forthcoming article, “the burden of proof falls on White.”

Stauffer and Annyston Pennington, a UVA English doctoral student who co-curated the exhibition, acknowledge that their evidence is circumstantial, but feel they have built the strongest case possible. “We’re just raising the conversation letting people decide for themselves,” Stauffer said. “The Library has been so supportive through this whole experience,” both in terms of conserving the portrait and updating it in the catalog to acknowledge the new scholarship, he said.

In that sense, the exhibition reminds the viewer that the Library’s archives are not static repositories, but instead living collections where curators, professors, and researchers are reinterpreting objects. “This exhibition blends visual art, art history and literary history,” said Pennington, who translated Stauffer’s article into the exhibition structure with visual aids and additional images.

“It shows off the work that’s often happening behind the scenes at the Library — of revisiting and reevaluating the collections,” Pennington said. “That reframing makes them valuable in an ongoing way.”

“Portrait of a Poet—Revisited: William Edward West’s Percy Bysshe Shelley” is on view through Nov. 5, 2023 in the First Floor Gallery of the Harrison Institute and Small Special Collections Library.